by Charles Redwine

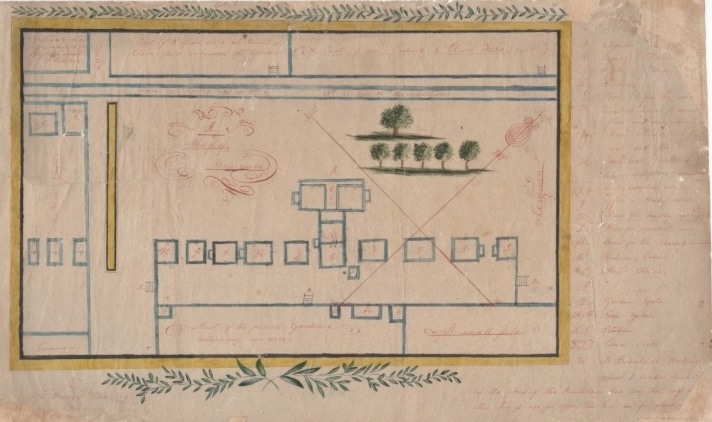

The Brainerd Mission and school, originally called the Chickamauga Mission, was founded in 1816 and existed until the forced deportation of the Cherokee in 1838. It was founded by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), an organization run by three Protestant denominations, including two Presbyterian and the Congregationalists. The church associated with the school was initially Presbyterian but soon switched its affiliation to Congregationalist. The school was not a formal part of the U.S. government’s plan of cultural genocide against Native Americans, but its history was marked by efforts at cultural erasure, abuse, exploitation, and miseducation. Its mission was supported by government officials; when he visited the mission in 1819, President James Monroe donated $1000 to promote its work.

The school’s student body included groups of students of various ethnic identities. One source indicates it was roughly evenly divided between Cherokees, white children of missionaries, and black students, both enslaved and free.

Initially, the Cherokee were generally supportive of the mission school. In an effort to keep their lands, the Cherokee had adopted a “plan of civilization,” in which they would adopt white culture, without the intention of abandoning their traditions. As a part of this plan, the attainment of English literacy was particularly important as it would allow them to understand treaties and business and legal documents. Relying on whites to interpret documents led to Native Americans being cheated by false promises.

Problems with the school soon led many Cherokees to oppose it. Problems with school included: total instruction in English, favoritism of ‘mixed-bloods’ over ‘full-bloods,’ abusive and culturally inappropriate corporal punishment, an emphasis on domestic arts and vocational training over academics, culturally insensitive attempts to teach male students to farm, and placement in unskilled over skilled apprenticeships. In the 1820s, opposition to the school led to a near total withdrawal of full-blood students, and by 1824, the school was forced to quit hiring new missionaries and teachers. After 1828, as efforts at ethnic cleansing accelerated, the traditionalist Cherokee’s opposition to the school was replaced by relative unity in common cause with the missionaries in opposition to forced deportation. In this effort the missionaries worked against the policy of expulsion favored by the majority in congress, even going to jail after the state of Georgia banned them from Cherokee lands. In the end the missionaries, of course, failed in this goal and so some accompanied the Cherokee in their forced march West.

In many ways the Brainerd Mission school was a failure. Only 100 of the 300 students who attended it attained full English literacy. Only a small handful of students converted to Christianity and the plan to “civilize” the people led to successful acts of resistance. It was not a bad thing that the school failed at many of its goals, but limited success in teaching literacy was a true failure. The missionaries were well intentioned, but the forced expulsion of the Cherokee was framed as “good for them” too. Therefore, their good intentions are a bad excuse.

The only remaining physical trace of the mission is its cemetery, as the rest of the site was destroyed by the development of Eastgate Mall and associated structures. The cemetery contains about 60 graves. Most marked graves are those of missionaries, while students and other Cherokees are mainly covered by stone slabs. The cemetery is maintained by the DAR and is open most daylight hours.

Sources:

https://findingaids.utc.edu/agents/corporate_entities/17

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brainerd_Mission